In time, I am being wheeled down a hall. Lights pass by overhead. I think that maybe the Lear Jet, maybe my surgery, maybe this hospital stay will ruin me economically for the rest of my life (as if my career hasn't already done so), but right now I don't care. I'm glad that Lear Jet was there, with its five man crew so comforting to me, to get me here as fast as possible.

In time, I am being wheeled down a hall. Lights pass by overhead. I think that maybe the Lear Jet, maybe my surgery, maybe this hospital stay will ruin me economically for the rest of my life (as if my career hasn't already done so), but right now I don't care. I'm glad that Lear Jet was there, with its five man crew so comforting to me, to get me here as fast as possible.I am not Catholic - when it comes to religion I am not anything but suspended in the big mystery - but I am damn glad the Catholics built this fine hospital, right here in Alaska, to care for me in this time of my need.

Thank you, Catholics! From the bottom of my heart - thank you!

I am damn glad to know that soon a surgeon of great skill will cut open my flesh and, using metal plates and screws, will put my broken bones back together. I want that surgery to come as soon as possible, because I am in pain, and nothing takes away that pain. Not the morphine drip, nothing.

They put me in what will be my recovery room and I long to sleep, but I can't. It hurts too bad. I was told that the humerous is the most painful bone to break and I broke it thrice. I was told that just a shoulder dislocation by itself is exceedingly painful, and I dislocated mine severely.

The pain is too great to sleep, even for one minute. "On a scale of one to ten, how would you rank your pain?" I am asked.

"Six," I lie, for I have no idea at all how to answer such a question.

I just long for morning, for the anesthesiologist, for the surgeon's knife, for then I will be unconscious and I will feel no pain at all.

Morning comes and I am wheeled into what they tell me is a cold room, because cold inhibits germs. "Are you cold?" I am asked repeatedly as I wait for the anesthesiologist. "Do you want a blanket?"

"No!" I answer. "I am hot. Do I have a fever?" I am assured that I do not, but I sweat profusely. I suppose the anesthesiologist must have come and we must have talked, he/she giving me this instruction or that, but I have no memory of it. One moment they are asking me if I am cold and I am telling them I am hot and then I am in a strange and blurry world filled with multiple beds peopled with occupants in various stages of consciousness as others look over them.

A middle-aged woman is looking over me, asking me questions and explaining things to me. I am wonderfully dazed and confused and I know that my body has just suffered trauma at a level that I have never before experienced but I am happy and the pain that I do feel seems hardly troublesome at all. I would try to recount some of my conversation with the woman, but it made no sense to me then and makes even less, now.

I am then wheeled into the same room that I did not sleep in the night before, the enclosure that will be my room for the next two days and nights as well. "Do you want anything?" I am asked.

"My camera," I answer. "I want my camera." They put it on the rolling table that stands alongside my bed. I close my eyes. When I open them, my son, Fire Kracker, stands by the window, looking at me. It is hard to pick my big, bulky, camera up with just my left hand, harder yet to manipulate it, but I do. I take his picture.

"Hi Dad," he greets, "how 'ya doing?"

"I'm dry," I rasp. My mouth and tongue feel like sandpaper. I can detect no moisture in there at all.

Then my daughter in-law, Stephanie, Fire's wife, pours me a glass of water. I gulp it down and plead for more. She says that soon, she will go home and bake me some oatmeal cookies.

Because she is in Arizona for the Apache Sunrise Dance, Sunflower cannot be here, but my room is quickly filled by my descendants. Here, son Toast Ed and grandson, Wry.

Because she is in Arizona for the Apache Sunrise Dance, Sunflower cannot be here, but my room is quickly filled by my descendants. Here, son Toast Ed and grandson, Wry. My daughter-in-law, Prickly Pear Blossom Kracker, changes Wry's diaper. My hospital room feels quite homey. My loved ones linger in and out all day, and into the night.

My daughter-in-law, Prickly Pear Blossom Kracker, changes Wry's diaper. My hospital room feels quite homey. My loved ones linger in and out all day, and into the night. Reflected in the window is my daughter, Tryskuit, and her boyfriend, Charlie, listening as daughter Nabysko reads Stephen Colbert. Nabysko wanted to bring me sushi, but I was not quite ready for sushi. I am, now, though.

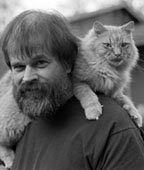

Reflected in the window is my daughter, Tryskuit, and her boyfriend, Charlie, listening as daughter Nabysko reads Stephen Colbert. Nabysko wanted to bring me sushi, but I was not quite ready for sushi. I am, now, though.Previous readers will recall how Nabysko wound up living in an apartment where cats are banned and how her boyfriend is allergic to cats. To help her weather these trials, a few months back she asked me for certain specific prints of the Kracker Cats, both living and dead. After I gave her this one of the late Little Clyde Texaco, who she so dearly loves, she hung it right by her bed.

Every night, she would look at the picture before going to sleep. On the day of my surgery, she removed the picture from the spot by her bed, brought it to my room, and taped it to the end post of my hospital bed. She eats an oatmeal cookie, baked by Stephanie.

And so it happened that the last image that I saw before I slid into a fitful sleep on the night following my surgery was this of Little Clyde Texaco. I took this image many, many, years ago as Clyde slept so peacefully in Nabysko's bed, tucked in between baby Mickey Mouse and another stuffed friend; tucked in by little Nabysko herself.

2 comments:

I loved Little Clyde Texaco's picture...Sweetest picture I have ever seen!!

Btw - Why did you lie when the hospital guys asked you to rank your pain? If I were you, I would have said 10 or more! :P

Yes - and Clyde was one sweet cat. You will learn all about him in the future, after fall, once I decide how I should really put a blog together and I do my relaunch.

As to my lie, any number that I would have chosen would have struck me as a lie.

I was asked this question many times, from when I first entered the emergency room in Barrow to just before I was discharged from Providence the second time.

Sometimes, I just wanted to scream "10!10! 10!" but I would always think of my late, older, brother, who broke his neck in a motorcycle accident and then spent the last 11 years of his life paralyzed.

By comparison, what I was going through seemed trivial. And there are many other examples - people burned in plane crashes, things like that.

I certainly do appreciate your interest and concern, Varsha.

Post a Comment