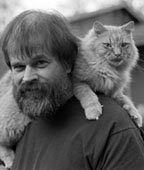

I took the above image of Diane Benson and her "Miracle Cat," Romeo in April of 2003 - one month after her son had been ordered into battle in Iraq, machine gun in hand. Accompanied always by Romeo, Diane was spending almost all of her time watching the cable news channels, desperate to know whatever she could about what her son, pictured in the photos she holds, faced.

As TV images flashed in front of her eyes, a series of three images that only she could see, played in her mind. In the first, she saw three-year old Latseen dash suddenly out into the road; in the second, she saw a car speed straight toward her son. In the third, she saw herself sprint straight into the path of the oncoming car, to place herself between it and her son; she wanted the driver to know that he was on a collision course with a human being.

Latseen must have loved that experience, for not long afterwards, the very young boy got into dog mushing himself and raced in one-dog competitions. Howard’s brother, George Albert, made Latseen’s first sled for him. The tiny boy was so eager to try it out that he did not wait for anyone to come and show him how, but instead hitched it to his dog when no one was looking, took off and wound up in a busy Chugiak intersection, where he caused a traffic jam.

Soon, Latseen graduated to three dogs – Max, Tantoo and Jake - all a mix of husky and wolf. “Sometimes we would go sit in the woods and watch him and those three dogs,” Diane recalled. “It was like watching poetry in motion. They were in sync.”

When he was 17, Latseen came to her. “Mom,” he told her, “I’m leaving. I bought a bicycle, I bought a plane ticket and me and Ben are going to Seattle and we’re going to ride down the west coast.”

“Oh,” Diane answered.

“This is it," she thought, "This is my son and he is going. I don’t know how to say 'no,' or if I should say 'no,'” Next, she thought, "Everybody has a moment when they need to be their own person." Diane stayed up most all of that night to sew a fleece vest for her son, as she knew he would need it.

And so Latseen set out on a journey that took him far from home and gave him many adventures, both good and bad. He was touched and moved by the goodness and generosity of so many of the people that he met along the way, but also amazed at the rottenness of some.

Now, as Diane nervously stroked Romeo and watched the late David Bloom of NBC follow the troops toward Baghdad, she recalled how she had once picked up the phone to hear the excited voice of her son. “Mom!" Latseen exclaimed, “I met a girl who can do 40 pushups!” That girl, Tasha, became his wife. Latseen then took on a “dead-end job” at a Washington sawmill and then he and Tasha had a son, Gage.

“Somebody has to do something,” he told his mother. So he joined the Army, determined to go to Afghanistan to punish the people who had did this terrible thing.

"Why can’t you join the fire department, the police department?" Diane had answered. "If its guts and glory you want, join the paramedics! Can’t you wait just a few months? Something else might come along and you might change your mind." But there was no talking him out of it.

So she and some close friends, including war veterans, hosted a special ceremony for Latseen, presided over by Tlingit Elder Richard Martin. The veterans and the elders told Latseen that being a warrior meant much more than just being sent out to kill, and that he would have to face many different trials. They gave him an eagle feather.”

Shortly afterward, he got his orders - not to Afghanistan, where the terrorists that he wanted to punish had been based, but to Kuwait. Iraq would be next.

“Other days, I just feel disbelief that any of this is going on.”

One day, Diane surfed into Fox News and was startled when Geraldo Rivera, broadcasting from South Baghdad, announced that he was with the 101st Brigade, First Division, “A” Company - Latseen's company.

Anxiously, she scanned every soldier's face, hoping to see her son. As the images kept going in and out of focus, she became irritated with the cameraman. While she did not see Latseen, she was struck by the faces of the soldiers that she did see. They were so young. "They looked like they were 18. They had little necks and puny legs.”

On TV, she saw the same images the rest of us did - the faces of the POW’s being interrogated, the dead bodies, a boy who lost both of his arms and most of his family. She wept when Lori Piestewa , Hopi, became the first Native American woman to be killed in action fighting for the United States government and she rejoiced when the POW’s who had traveled with her were rescued.

She admired the better reporters, particularly David Bloom, because she wanted to know as much as she could and they were the only ones telling her anything. She wanted to know just what was going on and why. Her son's life had been placed in severe danger. She wanted the clearest possible explanation as to why.

As to the soldiers, she felt they deserved support, whether one believed in the war or not. “You can’t blame the soldiers,” she explained. “They are at the mercy of government. We can change our government, but we can’t blame the soldiers."

As Diane described it in her speech, when Latseen first stepped back into Diane's house, " the first thing Romeo did was pop his furry little head up and meow at him."

As Diane described it in her speech, when Latseen first stepped back into Diane's house, " the first thing Romeo did was pop his furry little head up and meow at him."

She did not take a moment to think about her actions or to consider her own safety. She just did it, because she loved her son.

Now, in April, 2003, as 23 year-old Latseen fought in Iraq, Benson’s love remained powerful and her desire to protect every bit as strong, but it was impossible for her to fling herself between him and any bullets, rocket-propelled grenades, suicide bombers or roadside bombs that a hostile enemy might attack him with.

“You spend your life trying to protect a son or daughter,” Benson says, “then you are at war and they go off to fight and there is not a damn thing you can do.” If “war is hell,” then there is a special place of torment in that hell for the mother of a soldier engaged in combat, and Diane quickly found herself in that hell. All day long, as she nervously stroked Romeo, the images and sounds of bombs exploding and of guns firing filled her television screen.

I back up a bit now, a good 20 years before the war began, to the day that I took the above photo of Diane and Latseen as they posed with a truck owned by an outfit that Diane had once driven for. Her truck driving days were now over, but they had been dramatic. During construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, she had driven trucks up and down the 800-mile plus, often primitive, rugged, series of highways that linked the Arctic oilfields of Prudhoe Bay to the Prince William Sound port of Valdez.

No stretch of that road was more dreaded - particularly in winter - than Thompson Pass, which twists and climbs its way up and down through the rugged, towering Chugach Mountain Range. One winter day, a blizzard tore through the pass, hurling snow through the air so thick and furious that visibility dropped to near zero, yet, there was urgent need to get a certain truck load of goods through the pass.

It was a time when many men still did not like to see women do well in the "manly" occupations, and many of Diane's Pipeline, truck-driving colleagues often ridiculed her. Yet, when the call was issued for a volunteer to drive the load through the Thompson Pass blizzard, Diane was the only trucker to step forward. She got the load through.

Now, she was making a career as an actress, playwright and poet, and I was doing a story on her for the now-defunct Tundra Times Alaska Native weekly newspaper. Yet, her greatest passion was reserved for her son, Latseen.

Back to April, 2003: Diane could not pull herself away from the TV and Romeo would not leave her, except to visit the litter box. At night, she could not go to bed but instead stayed on the couch, close to the phone. At times, she had to step out to take care of necessary tasks and one day, as she fed the sled dogs, she began to hyperventilate. Her knees buckled beneath her and she collapsed upon the ground.

“With my son at war, I have been experiencing a kind of grief I have never known – and I have known grief intimately,” Diane told me. “It is the fear for your only child. You have raised that child you gave birth to and he is in a danger zone. You watch horrible things on TV and you know that your child is there.”

While she could get no information on Latseen's whereabouts or activities, countless images and memories cascaded through her mind. As he fought his way toward Baghdad, she again saw him at the age of three. This time, he sat on her lap as she sat in a basket sled hitched to a team of dogs owned by the late Howard Albert of Ruby, a Athabascan Indian trapper and Iditarod sled-dog racer.

Howard shouted commands to his dogs as they pulled the sled over the snow that covered the frozen Yukon River; sometimes he stood upon the back rails of the sled and kicked back with one foot to help the dogs propel it forward. Often, he would jump off the sled and jog behind it. The feet of the dogs churned the dry, cold, dust-like snow into the air, where the wind picked it up and blew it into the the faces of Diane and Latseen.

“The snow kept biting my face,” was how young Latseen described the experience.

Latseen must have loved that experience, for not long afterwards, the very young boy got into dog mushing himself and raced in one-dog competitions. Howard’s brother, George Albert, made Latseen’s first sled for him. The tiny boy was so eager to try it out that he did not wait for anyone to come and show him how, but instead hitched it to his dog when no one was looking, took off and wound up in a busy Chugiak intersection, where he caused a traffic jam.

Soon, Latseen graduated to three dogs – Max, Tantoo and Jake - all a mix of husky and wolf. “Sometimes we would go sit in the woods and watch him and those three dogs,” Diane recalled. “It was like watching poetry in motion. They were in sync.”

Latseen then moved up to seven and eight dogs and began competiting in races from Anchorage to Fairbanks, including the world championship Junior Fur Rendezvous. Sometimes he placed, sometimes he didn’t, but he did often enough to build up a large trophy collection.

However much Latseen loved dogs, he also loved the cat, Serendipity. Diane pictured how Latseen would bend down and Serendipity would climb up his arm to his shoulder, give him a head nudge, and then ride about the house on him.

She also remembered how Latseen would ride his bicycle everywhere. He loved duct tape and he was always duct-taping things to his bicycle – batteries, different kind of lights.

When he was 17, Latseen came to her. “Mom,” he told her, “I’m leaving. I bought a bicycle, I bought a plane ticket and me and Ben are going to Seattle and we’re going to ride down the west coast.”

“Oh,” Diane answered.

“This is it," she thought, "This is my son and he is going. I don’t know how to say 'no,' or if I should say 'no,'” Next, she thought, "Everybody has a moment when they need to be their own person." Diane stayed up most all of that night to sew a fleece vest for her son, as she knew he would need it.

And so Latseen set out on a journey that took him far from home and gave him many adventures, both good and bad. He was touched and moved by the goodness and generosity of so many of the people that he met along the way, but also amazed at the rottenness of some.

Latseen's bicycle journey ended in Arizona and then he worked his way back to Alaska by way of Las Vegas and Salt Lake City. He spent just one month at home, then ventured off to Washington state to join the Job Corps.

Now, as Diane nervously stroked Romeo and watched the late David Bloom of NBC follow the troops toward Baghdad, she recalled how she had once picked up the phone to hear the excited voice of her son. “Mom!" Latseen exclaimed, “I met a girl who can do 40 pushups!” That girl, Tasha, became his wife. Latseen then took on a “dead-end job” at a Washington sawmill and then he and Tasha had a son, Gage.

Then came another call. Diane heard something in her son's voice that she had not heard before. Anger. Pure, cold, hot, anger. Latseen Benson had just watched New York City's Twin Towers come down on TV. He had seen the hole blasted in the wall of the Penatagon, and the crater left in a field in Pennsylvania.

“Somebody has to do something,” he told his mother. So he joined the Army, determined to go to Afghanistan to punish the people who had did this terrible thing.

"Why can’t you join the fire department, the police department?" Diane had answered. "If its guts and glory you want, join the paramedics! Can’t you wait just a few months? Something else might come along and you might change your mind." But there was no talking him out of it.

So Latseen Benson, a Tlingit from Chugiak, with roots in Sitka and the great rainforest of Southeast Alaska, enlisted in the Army. Already fit and strong, he got through boot camp with little problem and begun to train for combat in Afghanistan. One of his fellow trainees was so frightened about the thought of Afghanistan that he went AWOL.

Not Latseen, “Latseen was gung-ho,” Diane recalled. “He was anxious to go. I was scared to death. I was sick to my stomach – I had knots in my stomach.” She talked to other parents who had children who had gone to war. "He won’t be the same person afterward,” she was told.

Before receiving his deployment orders, Latseen returned home for a visit. Whatever might lay ahead of him, Benson wanted her son to be absolutely certain of the love that she and others held for him. Whatever dangers he might face, she wanted him to be blessed with all the help he could get, not only physically, but spiritually.

So she and some close friends, including war veterans, hosted a special ceremony for Latseen, presided over by Tlingit Elder Richard Martin. The veterans and the elders told Latseen that being a warrior meant much more than just being sent out to kill, and that he would have to face many different trials. They gave him an eagle feather.”

Shortly afterward, he got his orders - not to Afghanistan, where the terrorists that he wanted to punish had been based, but to Kuwait. Iraq would be next.

On March 11, nine days before the war began, I received an email from Diane. “My son is I don't know where. He could still be in the U.S. or he could be overseas. About a month ago, he called and said that this was his official call to inform me that he was being deployed. I am not allowed to know when or where due to ‘national security.’ I have not heard from him since, and no longer have any way of communicating with him since his cell phone was disconnected. Some days I feel I am losing my mind over it.

“Other days, I just feel disbelief that any of this is going on.”

Then, at 8:23 AM, Sunday morning, March 16, 2003, Diane received a collect call from Kuwait. Would she accept the charges, the operator asked? “Yes! Yes! Yes!” Benson answered.“My heart was pounding! I was paranoid that we would get cut off. I was thinking, 'fibre optics, or whatever it was that was connecting us, don’t let me down.'”

Latseen could not give her any specifics about anything, but she recalled his graduation from boot camp at Fort Bliss, Texas, and how handsome he had looked in his uniform. She recalled the smell of that uniform, how well made it was, how perfect, and how strong and impressive he looked as he wore it.

Diane Benson could hear that same strength in Latseen’s voice now. As her fingers slipped through the fur of the purring Romeo, she found comfort in that.

One day, Diane surfed into Fox News and was startled when Geraldo Rivera, broadcasting from South Baghdad, announced that he was with the 101st Brigade, First Division, “A” Company - Latseen's company.

Anxiously, she scanned every soldier's face, hoping to see her son. As the images kept going in and out of focus, she became irritated with the cameraman. While she did not see Latseen, she was struck by the faces of the soldiers that she did see. They were so young. "They looked like they were 18. They had little necks and puny legs.”

On TV, she saw the same images the rest of us did - the faces of the POW’s being interrogated, the dead bodies, a boy who lost both of his arms and most of his family. She wept when Lori Piestewa , Hopi, became the first Native American woman to be killed in action fighting for the United States government and she rejoiced when the POW’s who had traveled with her were rescued.

She admired the better reporters, particularly David Bloom, because she wanted to know as much as she could and they were the only ones telling her anything. She wanted to know just what was going on and why. Her son's life had been placed in severe danger. She wanted the clearest possible explanation as to why.

“I think this is why so many people want black and white answers,” she told me. Yet, her experience in life and her artistic disciplines have taught her that answers seldom come in black and white.

As to the soldiers, she felt they deserved support, whether one believed in the war or not. “You can’t blame the soldiers,” she explained. “They are at the mercy of government. We can change our government, but we can’t blame the soldiers."

One day, as she sat with Romeo, she let her eyes wander from the TV to a collection of Latseen photographs that she had carefully spread in front of her. She picked up a portrait of her son and studied it intently.

One year later, Latseen returned from the war, alive and healthy. With the help of friends and relatives, many of them war veterans, and the Alaska Native Sisterhood, Diane sponsored a coming home ceremony for her son.

Shortly after it began, Latseen strode through the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage on his two good legs as he led a group of veterans on a walk around the auditorium.

The veterans came from many tribes, and many states. Two Lakota warriors from South Dakota honored Latseen with eagle feathers.

In her "welcome home" speech, Diane recounted the story of Romeo, who she described as "my best friend." She told how Romeo had helped her withstand her ordeal in a way that no human could. She recalled the miracle of how he survived his "terminal" illness after the vet had said there was no hope for him. "I whispered, 'I need my friend.' And that doggone cat stuck around."

As they pressed money to his head, his people honored Latseen with a special Tlingit name, one that means "Big Mountain."

Latseen danced in the way of the Tlingit. The Tlingits have two moietys, Raven and Eagle. Latseen is Eagle, but here, to keep things in balance, he wears a tunic and robe from the Eagles, his opposites.

As Diane described it in her speech, when Latseen first stepped back into Diane's house, " the first thing Romeo did was pop his furry little head up and meow at him."

As Diane described it in her speech, when Latseen first stepped back into Diane's house, " the first thing Romeo did was pop his furry little head up and meow at him."After the ceremony, I stopped at the house. Although the war clung to Latseen's mind, he could not speak of it in anything but the most oblique terms. Only those who had fought by his side could understand, he explained. His posture was hard, his face a mask.

"So how was it to come home and find Romeo still alive?" I asked.

"He's a cat," Latseen answered, indifferently, "he's just a cat."

"You can't tell me that," I said. "I know better."

Latseen jerked suddenly, as if my words had stunned him. The hard mask melted from his face, his posture softened, and a soft smile brightened his face. "He's one of the coolest cats I've ever known," he said, softly, affectionately. He then reached over and tousled Romeo's happy, furry, head.

Sadly, I, who almost always have a camera in hand, did not when that spontaneous pet happened. Later, with the exception of the wife who was leaving him, the whole family - Latseen, his son Gage and Diane did a little posing with Romeo.

It wasn't quite the same as that spontaneous moment, but this is what I got.

I wish that I could tell you that with this, Romeo's job was done. I wish I could tell you that, just as he had planned to do, Latseen's time in the Army came to it's scheduled end and he took his coast-to-coast motorcycle ride across the United States.

But that's not how it happened. About two weeks before his scheduled discharge, the Army told Latseen that he could not go. "Stop Loss," they called it. He received new orders - back to Iraq.

Romeo's toughest job still awaited him.

Coming in Part 4: A roadside bomb explodes in Iraq. Diane and Romeo on dark night in Chugiak, Alaska. Another miracle is needed.

6 comments:

This is a touching story.

Romeo is a wonderful cat. I love his color so much and I love his heart better.

Thank God Benson got back alive and kinky.

Do they spray money too in your place. Kinda see in the picture that they put money on Benson head.

You said "It was a time when many men still did not like to see women do well in the "manly" occupations"

I wonder why they consider such occupation has manly. Women dont even attempt to drive truck in Nigeria.

It's not funny really

How r you doing GK?

Bravo - now that was well worth the wait. It is so wonderful to learn about how other Americans hold fast to their own cultures and still give of themselves to their country.

I LOVE the B&W photo - such presence Diane has. And to be such a ground breaker for other women.

YEA! for Romeo .......

Taddie

Mahalo thank you (and Diane) for sharing Diane's and her family's story. We all need miracles, so it's wonderful to read about a real one. It brought tears to my eyes even while it stirred up that never-quite-buried anger i feel toward those politicians who make the decision to go to war, but whose sons or daughters rarely enlist...

I hope your shoulder is mending well.

LOVED the pic of Jim decorating the Xmas tree! :)

aloha

So so touching.....

I haven't read this touching beautiful story before. Thanks for sharing with us!!

Im pretty sure your my brother....

Latseen...

please respond!

email me

anockai@ups.edu

Post a Comment