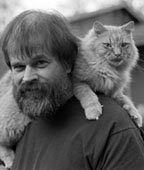

I don't know how this picture ever came to be. It is little me, with a kitten. When you finish this sub-series, you will understand why I do not know.

"Kitty! Oh, Kitty!" A young, exuberant voice erupted behind me. It was Nabysko, then four. She plopped herself down and stroked the kitten with such vigor that I feared she would hurt it. "Kitty likes us, she wants to live with us," she begged. "I like this kitty, too. Daddy, do you like this kitty?"

"I don't know," I answered. "Look how skinny he is. Maybe if we fatten him up, he might make a good meal by my birthday."

"Not to eat, you silly Daddy!" Nabysko chided. "To live here! To be our friend! Please, Daddy. Please. Mom likes Kitty, too."

"Your Mom," I said with conviction, "does not like this kitten. Your Mom does not like cats, she can't stand cats. She would never let us keep this cat. Anyway, it belongs to somebody else."

It is not that I was born with a hard heart concerning cats. Quite the opposite. I came into the world full of tenderness for all the furred and feathery little animals. I loved them all, and yearned for them to come and live with me. It seemed that they were equally eager to come and live with me, for they were always following me home - puppies, kittens, ducks, and owl.

My parents had other thoughts. Caught at the right time, they might yield to a puppy. But no other animals. Especially not cats - horrid, horrid cats. Vile animals. Disgusting animals. Once a cat got into a home, my mother would assure me, you could smell it there, forever.

Mom had been raised on a farm in southern Idaho, and here view of animals was totally utilitarian. Animals all had their place – chickens laid eggs, or went into the stewpot or onto the stove. Sheep gave wool and lambs were particular tender for eating. Cows gave milk and converted well into steaks, roasts, and hamburger.

Horses were good for moving cows around, and dogs could help with sheep. Cats were fine – in a barn or grain storage bin, where they could hunt and kill rodents before those rodents ate generous quantities of grain and pooped and peed in what they didn’t eat.

But there was one place that Mom believe no animal ever had a place in – the house. The home was a sanctuary for humans only. Animals were a desecration to a house. The concept of “pet,” or the idea that an animal, even a dog or a cat, could be a friend and not a worker was a concept that did not exist in her head.

Yet, just when I was about to start the second grade, I did manage to trick her into allowing me to adopt a kitten. Had it not been for that event, perhaps I would not have then grown up believing myself to be a despiser of cats. The brainwashing might never have occurred.

I will relate that story, but first I will tell you of another tragedy, one that speaks of how my love for all animals conflicted with my mother’s pragmatism.

The story involves a duck.

I had just turned six and I lived with my family of seven in a tiny house at the edge of the golf course in Pendleton, Oregon. It was rodeo time, and the carnival was in town. While there were many terrifying and thrilling rides, the center of my interest was the duck tent. Sitting in front of a couple of hundred of the cutest little yellow ducklings were a couple of hundred ash trays. To get a duck of his very own, all a boy had to do was toss a dime into one of the ashtrays, then pick out the duck of his choice. Heck. With all those ashtrays, how could a boy not win a duck?

Excitedly, I ran for my mother. She refused to give me even one dime. “Those duck people are just crooks,” she told me. “They are hucksters!” - ready to take every dime I had. It was rigged. I would never get a duck, but those hucksters would sure get my dimes.

Mom believed in teaching us kids responsibility while we were young, and so, at that tender age, I had already been sent into the street to sell newspapers. In fact, I had been doing so for two years. Unlike my brothers, I was shy, and a lousy salesman, and I never did take too kindly to the idea of responsibility. I sold very few newspaper, and seldom brought home more than two or three dimes. Once, I only made a nickel.

This so angered my boss that he slapped me. Then, as I crossed the bridge over the Umatilla on the way home, I dropped that nickel and it rolled off into the river.

But after seeing the baby ducks, I out my shyness aside. I went out and put the two hardest working days of my street-selling career, going so far as to walk into a couple of bars, where I had heard from my older brothers that a kid could not only make lots of sales, but collect some huge tips from drunken cowboys.

So I ventured into the cowboy bars carrying, my bag full of papers, and came out with a bagful of dimes.

On the final day of the carnival, I returned with my share of those of dimes, without my mother. If she had known about those dimes, she would have made me tithe ten percent of them to the church and put most of the rest in the bank – I could have kept just enough for a candy bar.

But these were duck dimes.

Knowing that putting a dime in one of the ashtrays was as easy as anything I could ever do, I indulged myself in a couple of carnival rides, then headed for the duck booth. I flung one dime after another into those ash trays and each time they slid right out and fell into the collection bin. I left with no dimes, no duck. With my heart broken, and tears forcing themselves from my eyes, I left the carnival grounds and ran, blurry-eyed, down a trail that ran along the banks of the Umatilla River.

Suddenly - a miracle.

"Quack!"

A little, yellow duck waddled up to me, and lifted its eyes to mine.

"Quack!"

It wanted to come home with me! It wanted to share my life! It wanted to be my best friend!

I took a step in the direction of home. It followed. Across the bridge and all the way home. And so as I walked home, the duckling followed me. I wanted to pick it up and carry it, but I reasoned that Mom could say that it was someone else's duck, and that in picking it up and carrying it home, I had done something dishonest, and I would just have to take it back to the duck tent. If it followed me, this was proof that nobody else wanted it, that it was my duck.

This logic was lost on Mom.

“No, Grahmmy!” she said, “this duck is not yours. It belongs to someone else. We must find out who and then you can return it to them.” It did not take them long to find somebody else willing to be that person. Just a few houses up the road lived a kindergarten mate of mine. Yes, his mother said, he had landed a dime in an ashtray, and had won a duck. He loved that duck so much! He brought it home and he just adored it, and the duck adored him, but, somehow, he had lost the duck. How his heart had broke. Why, this duck that sweet little Grahmmy found, this is the very duck! This is Larry’s duck!

Yeah, right. Even as a five year old, I knew that a little duckling like that would not have left this house, waddled all the way back to the river, crossed the bridge, then continued on alongside the riverbank until it almost reached the carnival grounds.

No. This was not Larry’s duck. This was my duck. Even so, Larry rejoiced, and took the duck into his home. My heart was broken now, and all the talk about how I had done the right thing, and how good this was for my character, could not mend it.

A kitten could, though, and I would soon have one.

But after seeing the baby ducks, I out my shyness aside. I went out and put the two hardest working days of my street-selling career, going so far as to walk into a couple of bars, where I had heard from my older brothers that a kid could not only make lots of sales, but collect some huge tips from drunken cowboys.

So I ventured into the cowboy bars carrying, my bag full of papers, and came out with a bagful of dimes.

I met this cat along the way, in Washington state, being admired by a phony duck. The experience was a bitter reminder of the ordeal that I had faced as a child.

On the final day of the carnival, I returned with my share of those of dimes, without my mother. If she had known about those dimes, she would have made me tithe ten percent of them to the church and put most of the rest in the bank – I could have kept just enough for a candy bar.

But these were duck dimes.

Knowing that putting a dime in one of the ashtrays was as easy as anything I could ever do, I indulged myself in a couple of carnival rides, then headed for the duck booth. I flung one dime after another into those ash trays and each time they slid right out and fell into the collection bin. I left with no dimes, no duck. With my heart broken, and tears forcing themselves from my eyes, I left the carnival grounds and ran, blurry-eyed, down a trail that ran along the banks of the Umatilla River.

Suddenly - a miracle.

"Quack!"

A little, yellow duck waddled up to me, and lifted its eyes to mine.

"Quack!"

It wanted to come home with me! It wanted to share my life! It wanted to be my best friend!

I took a step in the direction of home. It followed. Across the bridge and all the way home. And so as I walked home, the duckling followed me. I wanted to pick it up and carry it, but I reasoned that Mom could say that it was someone else's duck, and that in picking it up and carrying it home, I had done something dishonest, and I would just have to take it back to the duck tent. If it followed me, this was proof that nobody else wanted it, that it was my duck.

This logic was lost on Mom.

“No, Grahmmy!” she said, “this duck is not yours. It belongs to someone else. We must find out who and then you can return it to them.” It did not take them long to find somebody else willing to be that person. Just a few houses up the road lived a kindergarten mate of mine. Yes, his mother said, he had landed a dime in an ashtray, and had won a duck. He loved that duck so much! He brought it home and he just adored it, and the duck adored him, but, somehow, he had lost the duck. How his heart had broke. Why, this duck that sweet little Grahmmy found, this is the very duck! This is Larry’s duck!

Yeah, right. Even as a five year old, I knew that a little duckling like that would not have left this house, waddled all the way back to the river, crossed the bridge, then continued on alongside the riverbank until it almost reached the carnival grounds.

No. This was not Larry’s duck. This was my duck. Even so, Larry rejoiced, and took the duck into his home. My heart was broken now, and all the talk about how I had done the right thing, and how good this was for my character, could not mend it.

A kitten could, though, and I would soon have one.

Next up in Sub-series, Part B of Part 3: Betrayed by a kitten

2 comments:

You tell your stories so well that I feel I'm right there with you, feeling your emotions and your pain. I can't wait for the next instalment. That duck would have been so happy with you but, on the other paw, your mother might have cooked him and that would have broken your heart still more. xxx

It would have broken my heart. I wonder how it would have tasted?

Post a Comment